- TOP

- 国際人権基準の動向

- FOCUS

- December 2022 - Volume 110

- Protecting Internet Freedom in Asia-Pacific's Cyberspace

FOCUS December 2022 Volume 110

Protecting Internet Freedom in Asia-Pacific's Cyberspace

Over the past four years, the Asia-Pacific region witnessed a considerable increase [1] in its online population with 2.56 billion users by 2021, the largest number of internet users globally.[2] Not to mention the two economic giants of the region, China (939.8 million internet users) and India (624 million internet users), which are currently leading the number of internet users worldwide.

With the omnipresence of the internet in the region, securing the freedom of individuals while using the internet has become a critical issue for authorities across Asia-Pacific.

Regrettably, the advent of COVID-19 pandemic led to a plummeting trend in the score of internet freedom gauged by Freedom House in its latest report[3] in a handful of Asia-Pacific economies and could possibly continue to worsen in the post-pandemic era. This report is an annual human rights-based study focused on the digital sphere, gauging three main aspects: (1) Obstacles to access, (2) Limits on content and (3) Violations of user rights in cyberspace in seventy countries worldwide. The score is measured on a 100-point scale, so the lower the score gained, the less freedom enjoyed by people in a country while surfing the digital sphere.

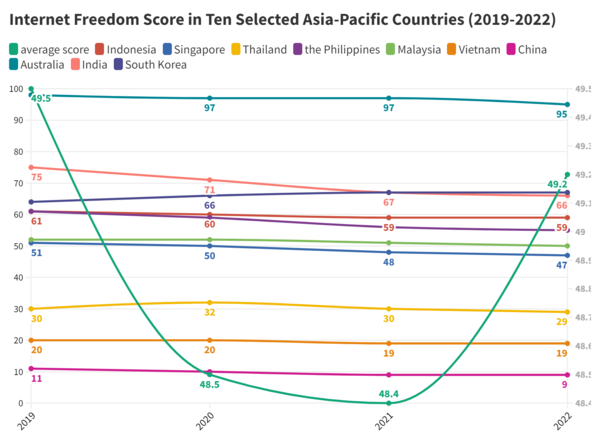

As shown in Figure 1 below, internet freedom tended to decline in the entire ten selected Asia-Pacific countries, namely, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, China, Australia, India, and South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 before making a slight improvement in 2022.

In 2019, a year before the COVID-19 pandemic, the ten selected Asia-Pacific countries could merely obtain an overall score of 49.50 out of 100 or categorized as "partly free," before making a marked decline to 48.50 and 48.40 out of 100 in 2020 and 2021 respectively. Of the ten selected countries, Australia ranked at the top (with an average score of 76 or categorized as "Free"), while China gained the least (with an average score of 10 or categorized as "Not Free"). While eight of them faced a downturn trend (Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines, Vietnam, Australia and India), two others had stagnant internet freedom score (China and Thailand) since the early days of the pandemic (2020) compared to previous scores in 2019.

Figure 1. Internet Freedom Score in Ten Selected Asia-Pacific Countries (2019-2022)

Source: Authors' formulation based on Freedom House's Internet Freedom Score Report 2019-2022.

Digital Surveillance, Censorship and Data Breaches

The restriction of freedom on the internet can undoubtedly be attributed to the stringent COVID-19-related policies enacted by authorities in Asia-Pacific countries during the pandemic. The authorities across the region are considerably exerting digital technologies to create resilience against the virus. However, these actions constitute a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, utilizing digital tools would improve governments' effectiveness in raising people's awareness of the pandemic and mitigating the spread of the virus. On the other hand, the excessive power of governments is inclined towards tightening control over cyberspace, resulting in the rise of digital surveillance or online media censorship that is commonly justified as necessary in curbing the spread of COVID-19 and maintaining domestic socio-economic stability.

For the latter, state surveillance practices have been evident in the use of digital-based health platforms across countries in the region, resulting in the huge potential of mass surveillance to ensure public health and safety. South Korea[4] has developed one of the world's most comprehensive contact tracing systems using closed-circuit video footage, mobile phone location tracking, and credit card transaction logs. The national digital health code system plan[5] of the Chinese government, which is already employing cutting-edge technologies such as facial recognition, Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking and drones, is seen as a concrete form of digital authoritarian practice. Coupled with the controversial zero-COVID policy, it is not surprising that public uneasiness in China has culminated in the emergence of unprecedented "blank paper" mass protests lately.[6]

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a justification for governments to censor and control online space to maintain domestic stability and to avert proliferation of online fraud schemes that victimize people. Freedom House has found that at least twenty-eight countries have blocked users and platforms to suppress unfavorable health statistics and criticism of the government's handling of the pandemic. [7] Cases of control of online space can be found in several Southeast Asian countries like the imposition of uniformity[8] in online news by the Vietnamese government and the tendency to control[9] news coverage by the Singaporean government. Also, Amnesty International reported that Thailand, as part of the Emergency Decree invoked in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, declared that "publishing or distribution of information about COVID-19 which is misleading and may induce public anxiety"[10] is prohibited and could lead to imprisonment.

Another crucial issue that should be considered by governments across Asia-Pacific is the personal data protection mechanism since citizens' data are prone to leak in countries across the region. During the pandemic, countries like Singapore[11] and Indonesia[12] faced severe data breaches linked to their national public health system, endangering the safety of personal data. Amidst the extensive use of digital technologies, cyber resilience and personal data protection should be prerequisites before applying any digital-led innovation in public services in the future.

Why is this Happening and How to Move Forward?

We can see a general trend of global decline of digital freedom and the rise of digital authoritarianism. Erol Yaybroke of the Center for Strategic and International Studies stated, "Established democracies lack a consistent and collective strategic approach to combat authoritarian use of digital and online space, even as they often preserve and promote advantageous elements of technology."[13] This is because controlling the online space is in and of itself a double-edged sword as earlier stated.

How can a fair and democratic government control a space without limiting the freedom of the platform itself? As we have seen with data collection and misuse of digital regulation, governments can justify their actions in the name of protecting their citizens; however, defending the citizens can be perceived as somewhat authoritarian. This is especially apparent during COVID-19 pandemic, where more than ten countries have shut down the internet, while twenty countries[14] have increased or added new laws limiting online communication.

So, what can the government do to ensure digital freedom? Maintaining a democratic and open internet is a key factor. The first step to this is data protection. Countries are now taking steps to ensure that citizens' data are safe. The best example is the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR is the pinnacle of data protection rules, the most stringent in the world. By making businesses accountable for handling and treating this information, it aims to offer customers control over their data.[15] The Asia-Pacific region has much catching up to do with its European counterpart. Indonesia, for example, recently ratified the first comprehensive personal data protection law in September 2022.[16] Data protection is an essential first step when it comes to ensuring digital freedom, as it will serve as the foundation for a safe environment regarding digital platform usage.

Maintaining a democratic and open internet is imperative to any democratic regime. Exercise of freedoms has been restricted in recent years due to one factor or another. Not only must the government ensure that their citizens' privacy and data are protected, but they must also protect freedom of assembly and freedom of expression. These freedoms are no longer confined to the physical realm but have extended to the digital platforms. It is the right of everyone to voice their opinion and meet with like-minded individuals without fear. This is the foundation and pillar of a healthy, free digital space.

Albert J. Rapha is a research affiliate at the Centre for Policy Studies and Development Management (PK2MP) at Diponegoro University, Indonesia.

Aufarizqi Imaduddin is currently a graduate student at the School of Business and Management, Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia.

For further information, please contact: Albert J. Rapha, e-mail: albertjehoshua@gmail.com.

[1] Number of online users in the Asia-Pacific region from 2017 to 2021, Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/1040574/apac-number-of-online-users/.

[2] Number of internet users in the Asia-Pacific region as of January 2021,by country, Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/265153/number-of-internet-users-in-the-asia-pacific-region/#:~:text=As%20of%20January%202020%2C%20China%20ranked%20first%20with,users%20worldwide%2C%20reaching%20over%202.3%20billion%20in%202019.

[3] Countering an Authoritarian Overhaul of the Internet, Freedom House, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2022/countering-authoritarian-overhaul-internet.

[4] Mark Zastrow, South Korea is reporting intimate details of COVID-19 cases: has it helped?, Nature, 18 March 2020, www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00740-y.

[5] Iris Zhao, China's planned national digital health code system raises concerns over state surveillance, ABC News, 26 November 2022, www.abc.net.au/news/2022-11-26/china-plan-for-national-digital-health-code-system/101690448.

[6] China's protests: Blank paper becomes the symbol of rare demonstrations, BBC, 28 November 2022, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-63778871.

[7] Information Isolation: Censoring the COVID-19 Outbreak, Freedom House,

https://freedomhouse.org/report/report-sub-page/2020/information-isolation-censoring-covid-19-outbreak.

[8] Dien Nguyen An Luong, Vietnam Wants to Impose News Uniformity Even in Cyberspace - at What Cost? Fulcrum, 19 October 2022, https://fulcrum.sg/news-uniformity-in-cyberspace/.

[9] Freedom on the Net 2022 - Singapore, Freedom House, https://freedomhouse.org/country/singapore/freedom-net/2022.

[10] Thailand: "They are always watching": Restricting freedom of expression online in Thailand, Amnesty International, 23 April 2020, www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa39/2157/2020/en/.

[11] David Sun, Fullerton Health vendor's server hacked; personal details of customers sold online, The Straits Times, 25 October 2021, www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/fullerton-health-vendor-hacked-personal-details-of-customers-sold-online.

[12] Hackers leak personal data of 279 million Indonesians, The Star, 22 May 2021, www.thestar.com.my/aseanplus/aseanplus-news/2021/05/22/hackers-leak-personal-data-of-279-million-indonesians.

[13] Promote and Build: A Strategic Approach to Digital Authoritarianism, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 15 October 2020, www.csis.org/analysis/promote-and-build-strategic-approach-digital-authoritarianism.

[14] Bahia Albrecht, Gaura Naithani, Digital authoritarianism: A global phenomenon, https://akademie.dw.com/en/digital-authoritarianism-a-global-phenomenon/a-61136660.

[15] Jake Frankenfield, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Definition and Meaning, Investopedia, 11 November 2020, www.investopedia.com/terms/g/general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr.asp.

[16] Hunter Dorwart and Katerina Demetzou, Indonesia's Personal Data Protection Bill: Overview, Key Takeaways, and Context, Future of Privacy Forum, https://fpf.org/blog/indonesias-personal-data-protection-bill-overview-key-takeaways-and-context/.