- TOP

- 国際人権基準の動向

- FOCUS

- December 2021 - Volume 106

- International Marriage in Japan: Russian-Speaking Women Married to Japanese Men

FOCUS December 2021 Volume 106

International Marriage in Japan: Russian-Speaking Women Married to Japanese Men

In this article I introduce my co-authored book, The Politics of International Marriage in Japan, which focuses on unraveling the web of historical, governmental, and cultural influences on international couples. The book discusses life trajectories of marriage migrants in Japan from different regions (former Soviet Union, Asia/Philippines and the West), and here I focus on Russian-speaking women from former Soviet Union (FSU) countries who married Japanese men.

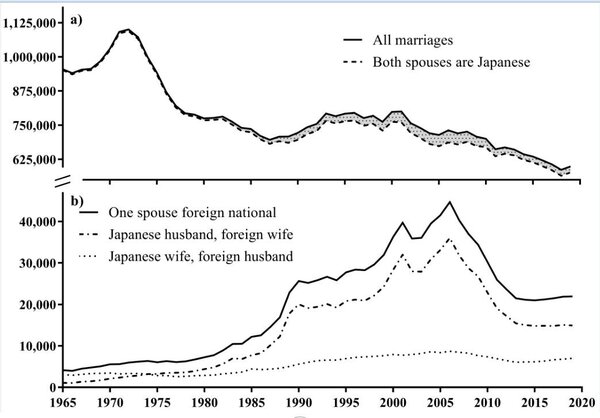

International marriages in Japan grew rapidly in the past two decades (Figure 1). One of the large groups of marriage migrants are women from FSU--mainly, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. There are no exact estimates of Russian-speaking females married to Japanese men. However, there were 16,310 nationals (9,318 or 57 percent females) from the abovementioned countries, among these 1,450 were "spouse of Japanese national" and 5,459 "permanent resident" status holders (E-Stat: Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan 2020b). Since many foreign spouses acquire permanent residence after at least three years of marriage and residence in Japan, and women constitute about sixty percent among these, I estimate that there were approximately 3,500-4,000 (50-60 percent) FSU female marriage migrants in 2019.

Figure 1. Trends in International Marriages in Japan,

Figure 1. Trends in International Marriages in Japan,

created by Kim based on E-Stat: Portal Site of

Official Statistics of Japan (2020a)

Paths to Marriages with Japanese Men

From the 1990s, unions between FSU women and Japanese men grew, driven by the collapse of the USSR, which resulted in the freedom of movement to and from post-Soviet countries. One of several paths where FSU women and Japanese men met was a consequence of the entertainment industry in Japan that attracted large numbers of Slavic FSU women. Alongside this was the spread of marriage introduction agencies and their development into internet dating sites. According to estimates, there were at least three hundred marriage agencies in Russia that operated or had online presence (Ryazantsev and Sivoplyasova 2019). An alternative path originated from the increased presence of Japanese businesses and tourists in FSU countries and increasing interest in Japanese language and culture among Russian-speaking people.

Ryazantsev and Sivoplyasova (2019) point out that "Russian wives" became a special sociocultural phenomenon, usually describing Slavic women from post-Soviet countries. "Russian wives" are characterized by their orientation toward husband and children; readiness to give up career for family; ability to manage household, which are attractive traits for foreign grooms. On the other hand, Russian women are attracted to foreign men for their image as being able to support the family financially, leading a healthy lifestyle and not being addicted to alcohol (Ryazantsev and Sivoplyasova 2020).

Spousal Choices

One of the findings is that the place where the relationship was initiated--Japan or overseas--significantly shaped couples' decisions on where to live and how to organize their households. As such, the major reasons for couples that met overseas to settle in Japan were economic and familial responsibilities. Many spouses considered that the husband's earning power and the quality of life would be better in Japan. Most of the FSU wives were either homemakers or worked part-time, while their husbands were the main breadwinners. Even though there were cases where Japanese men could speak foreign languages and had experience working overseas, in the majority of cases, Japan was chosen as the country of settlement due to the husband's career and the perceived lack of opportunities in women's countries. In contrast, couples that met in Japan were often a result of FSU women's involvement in the Japanese entertainment industry, with many women and their husbands reporting no prior intentions to marry foreign nationals. Women in such marriages were more or less familiar with life in Japan and were willing to settle here.

Love

The book also addresses the question of love and its various representations. The focus here was not on the existence of genuine love, but the romanticized view of love and concerns of authenticity, often imposed by the immigration regime and popular media. Even though there were individual wives in constrained family situations, most still claimed to have romantic feelings toward their spouses. As such, FSU wives voiced the security that Japanese men represented and the trust in their family support, contrasting with men back in their home countries. Others claimed that the abundance of beautiful women in the FSU made it hard to compete for the smaller number of men that would provide them with the family life they imagined. Being chosen from among other women by the future (Japanese) husband was a perfect scenario for them to fall in love. As for Japanese husbands and their reasons for choosing an FSU wife, one participant pointed out that he was attracted to the idea that his wife was not too traditional, but also not too emancipated, she was "fifty/fifty." Also, some men pointed out that they were attracted to Russian culture and literature, while others were attracted to Slavic women's appearance.

Family Affairs

Another point of interest is negotiations over household organization, bilingual/bicultural education of mixed-heritage children and international divorce. The book introduces examples and situations in which international couples negotiate family customs, child rearing, and each other's role in the family. A major finding is that though it tended to be a husband's career needs that informed family roles, the family lifestyle tended to be organized based on wives' preferences. As for parents' educational strategies, FSU wives chose the Japanese school system. While it allowed both children and their mothers to gain fluency in the Japanese language, Russian language skills needed constant support by communicating in it inside the home, regular visits to FSU and other strategies. Needless to say, the difficulty of supporting fluency in both languages in many cases led to monolingualism or passive bilingualism. And finally, the book introduces cases of FSU women's international divorce and complications they faced when their marriage collapsed. Hitherto there has been little information on what happens during and after divorce; therefore, I aimed to fill this gap in the research. Despite (perhaps fortuitously) having a relatively small number of participants whose life courses I could follow, I hope the information on their experiences will contribute to the knowledge of international marriage in Japan.

Future Research

During the time of writing this book, there have been changes in the combination patterns of international spouses: there are fewer female entertainers, but more young people come to study and work in Japan; there is a visible increase in the non-Asian population, specifically Western men, who come to Japan as English language teachers; there are exponentially more tourists traveling to Japan; there are more ways for women and men to meet across borders through dating apps. All these changes will modify international marriages in the near future. However, this new diversity within such marriages cannot be addressed without considering the individual, structural, and global politics of international marriage migration.

Viktoriya Kim is a Specially Appointed Associate Professor at the School of Human Sciences, Osaka University. She specializes in international marriage migration, multicultural policies, and integration issues of foreign residents in Japan. Her current projects involve comparative research on Russian-speaking female marriage migrants in South Korea and Japan, foreign residents and multicultural community building in Japan during COVID-19, and integration of third-generation Koreans in Central Asia.

For further information, please contact: Viktoriya Kim, mviktorishka5@gmail.com, www.linkedin.com/in/viktoriya-kim-80959520b.

References

E-Stat: Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan. 2020a. "Vital Statistics / Vital Statistics of Japan Final Data Marriages." 2020, www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&query=人口 婚姻 国籍&layout=dataset&stat_infid=000031981584&metadata=1&data=1.

------. 2020b. "Zairyū Gaikokujin Tōkei [Statistics on Foreign Residents in Japan]." 2020.

Ryazantsev, Sergey, and Svetlana Sivoplyasova. 2020. "'Russian Wives': At the International Marriage Market," Sotsiologicheskie Issledovaniya 2 (2): 84-95. https://doi.org/10.31857/S013216250008496-8.

Ryazantsev, Sergey V., and Svetlana Yu. Sivoplyasova. 2019. "Marriage Emigration of Russian Women: Causes, Trends, Effects," The Journal of Social Sciences Research, no. 56 (June): 1060-66. https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.56.1060.1066.