- TOP

- 国際人権基準の動向

- FOCUS

- March 2019 - Volume 97

- Kamagasaki: Renewing an Urban Poor Community

FOCUS March 2019 Volume 97

Kamagasaki: Renewing an Urban Poor Community

Kamagasaki is a well-known yoseba in Japan. A yoseba is “a place where employers and laborers directly meet for possible employment.”1 These workers are known as “day laborers” because they seek jobs on a daily basis. Other yoseba existed in Japan including “Sanya in Tokyo, Kotobuki in Yokohama, Sasajima in Nagoya, [and] Chikko in Fukuoka.” But Kamagasaki is considered as the biggest yoseba.2

Kamagasaki has become known as an old community of day laborers and homeless people in Osaka city.

Kamagasaki: An Old Slum Area

The Kamagasaki Community Regeneration Forum provides a brief history of Kamagasaki:3

Kamagasaki originates in Nago Town (Naga Town) known as a yoseba from the early Edo Era [17th century] and a slum area from pre-modern times; Nago Town moved to Kamagasaki in the occasion of the 5th Domestic Industrial Exhibition in 1903. Kamagasaki once vanished after the air raid on Osaka [during the war]; however, it restarted as a black market and the massive yoseba, as it is today, was formed during the time of intensive economic growth. Kamagasaki functioned as the laborers' market to support [the] Japanese economy (especially for the construction industry) at least till 1991 when bubble economy ended, even though there were many problems.

Sen Arimura in his illustrated history of Kamagasaki (The History of Kamagasaki: After 1945) provides further information on the history of Kamagasaki:4

In the 1950s, Kamagasaki was a typical slum, inhabited by many victims of World War II... The main street was lined with doya (cheap lodgings), behind which people built poor, wooden shanties that often extended onto the street. It was like a maze. The rows of shanties below the Nankai train line overpass were dubbed the "Nankai Hotel." People frantically did anything they could to make a living: they delivered packages, bought scraps of clothing, picked up garbage, shined shoes, sold cigarettes, or ran open-air baths. The cheap drinking establishments were likely frequented by local laborers as well as workers from the docks.

Day Laborer Recruitment Site

The construction boom in Japan that started in the 1960s till the early 1990s had a very significant impact on Kamagasaki. Arimura explains the 1960s situation:5

During [the 1960s], the day laborer recruitment site was on the south side of the Nankai train line... This was a period of rapid economic growth for Japan, and many farm workers and workers from mines that closed down flocked to Kamagasaki. The population of single male day laborers suddenly swelled past 10,000, a great many of them in their 20s and 30s. In addition to construction work, there were also many jobs in transportation (related to dock work) and manufacturing.

The Osaka city government changed the name of the place to Airin District in 1966. The Osaka city government decided to develop Kamagasaki as “supply center for day labor ... to eliminate labor force shortages for the construction of the venue for the 1970 Japan World Exposition, in Osaka, with the effective use of day workers.”6 This measure changed the character of Kamagasaki:7

As a result, the number of day workers drastically increased, and family households moved outside the district. This was how the Airin District, which had been called a slum before, gradually was transformed into a flophouse area for unmarried men.

In the mid-1970s while the percentage of men in the district increased to 70%, the percentage of juveniles decreased to 10%. In the bubble economy period around 1990, men accounted for 85%, and the juvenile population was only 2% (Osaka City University Urban Research Plaza, 2011).

The Osaka city government constructed in 1970 the Airin Center building, where the Nishinari Labor and Welfare Center and the Osaka Socio-Medical Center Hospital that served the day laborers were located.

Arimura writes that the Osaka city government started in the 1970s the “abure techou (unemployment card) system,” which helped the day laborers during periods of unemployment.8

In the 1980s,9

Airin District experienced an economic boom and the number of day workers drastically increased. Especially in the bubble economy period from the late 1980s to early 1990s, huge public projects in the Kansai region, such as the construction of the Kansai Science City, Kansai International Airport, and the Akashi-Kaikyo Bridge started. Also the number of private projects for buildings and condominiums increased. This is why Airin District became very lively.

Workers from other countries started to come to Kamagasaki from “late 1980s”10 to work as day laborers.

Partially closed Airin Center

The bursting of the bubble economy in the 1990s led to the unemployment of many day laborers, and further increased the number of homeless people in Kamagasaki. In the 2000s,11

due to the increase in the number of people receiving public assistance, the area became a town of welfare (a poor area where unmarried male workers had a place to settle down).

In 2019, Kamagasaki retains a significant number of homeless people and aged workers. The Airin Center has been partially closed, with its medical facility still in operation. Other places in Kamagasaki have hotels with cheap room rates, causing the increasing number of tourists in the area.

Renewal of Kamagasaki

Civil society organizations have been working with the residents in Kamagasaki to find ideas on the renewal of the area. One idea calls for the "promotion of community building that makes fresh starts and challenges possible by the creation of a cooperative community focal point (service hub) for providing housing, work, health care, social and other services." This “Nishinari Service Hub” concept is based on the accumulated experiences of the members of the civil society that have been providing services to the Kamagasaki residents for many years.12

On the other hand, the Osaka city government launched its Nishinari Special Zone Project in 2012. The city government sought the support of the civil society (specifically the Haginochaya Community Creation Conference and the Kamagasaki Community Regeneration Forum) in defining the appropriate measures for the renewal of Kamagasaki.13

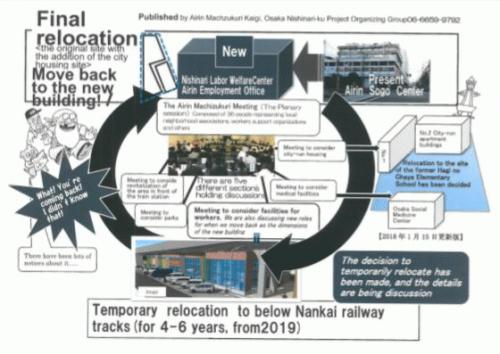

Kamagasaki residents and members of the civil society came together to discuss ideas on the renewal of Kamagasaki. They formed the Airin Machizukuri14 Kaigi (Airin District Community Development Forum), which started to hold meetings in 2014.15 They agreed to adopt a vision of creating a “Collective Town” where people treat the place where they live in as their home and where safety and social welfare opportunity are made available mainly through their own efforts.16

The Airin Machizukuri Kaigi has thirty-six members consisting of leaders of neighborhood associations, support organizations for different sectors (workers, children, women), association of budget hotels, association of shopping arcade shop owners, as well as university professors and prefectural, city and district authorities. It has five sections that cover public housing, healthcare facilities, vitalization of the train station area, labor facilities, and parks & area management. Each section holds meetings to discuss its own proposals.17

The Osaka city government decided to demolish the Airin Center building due to safety concerns. During the 5th Airin Machizukuri Kaigi, held on 26 July 2016,18 with the attendance of the Governor and the City Mayor of Osaka, the construction of a new Airin Center building was officially decided.19 A position paper of the panel of experts states the plan:20

The unemployment and labor center moved in April 2019 to a temporary site, and was scheduled to move back to the site of the former center in 2025. The medical center was supposed to move in to the new building in 2020. The City housing unit 1 is in the process of moving in and unit 2 is schedule to move in 2021.”

In its 26 July 2017 meeting, the Airin Machizukuri Kaigi came up with several proposals such as constructing a new building for the Airin Center in the same place where it was located, constructing a building for the Osaka Socio-Medical Center Hospital in the former Hagi no Chaya Elementary School ground, and the construction of housing facilities.21

The panel of experts has taken the stand of making the renewal of Kamagasaki as inclusive as possible, it states:22

For the past twenty years, we have worked for community development and [the solution of] the difficult problems of this community with a diverse group of organizations. [After] the government’s proposal for the “Nishinari Special District” [was raised], we have worked together to overcome our differences in order to provide a participatory bottom-up alternative to the top-down plan for slum clearance. Now, in the face of changes brought by the wave of redevelopment in the area around the station, we are working to maintain the inclusivity of the community and use its resources to create a community where starting over is possible.

[The Panel stresses that the] cooperation among the laborers, community organizations, community residents and local government is essential.

Pursuant to this perspective, the Panel of Experts submitted to the Osaka city mayor the “Nishinari Special District Plan - Community Development Vision 2018-2022; Opinion by a Panel of Experts” on 31 October 2018.23

Machizukuri Conference Poster

The Plan offers six suggestions for the renewal of Kamagasaki:

1. Promoting the development of a diverse cross-cutting town where people can make another try [at improving their lives] by connecting work, housing and welfare via the “service hub;”

2. Aiming to build a “collective town” [by] sharing various things in the town through creating spaces where people can feel they belong (resilient town development);

3. Community where the voices of children can be heard everywhere, and where children can be raised easily and can grow easily;

4. Friendly! Funny! Improving [its] image as a typical town of Osaka (Archives linking town’s history and culture with education);

5. Building a collaborative system [that links] local bottom-up approaches and [supports] cooperation among administrative bureaus (horizontal collaboration) to embody the approaches;

6. Aiming toward a town development utilizing external forces24 flexibly in order to prevent adverse effects due to gentrification.25

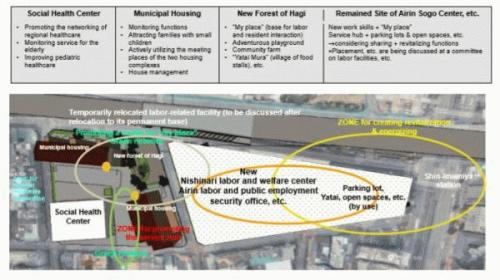

One section of the plan provides for renewal proposals for the different areas of Kamagasaki such as the following:

1. Social Health Center

a. Promoting the networking [for] regional healthcare;

b. Monitoring service for the elderly;

c.Improving pediatric healthcare;

2. Municipal Housing

a. Monitoring [of the housing facilities];

b. Attracting families with small children;

c. Actively utilizing the meeting places of the two housing complexes;

d. [Housing] management;

3. New Forest Hagi

a. "My Place" (base for [interaction among laborers and residents]);

b. Adventurous playground;

c. Community farm;

d. "Yatai Mura" (village of food and stalls, etc.);

4. Site of Airin Sogo Center

a. [Place for acquiring n]ew work skills + “My Place;”

b. Service hub, parking space and open spaces, etc. - considering [their] sharing and revitalizing functions;

c. Placement [for work], etc., are being discussed at a committee on labor facilities, etc.

Illustration of the proposals for the renewal of the different areas of Kamagasaki26

The renewal of Kamagasaki based on the participation of the different residents in the area and for the benefit of them all (specially the day laborers and the homeless) is an idea that has to be realized.

Jefferson R. Plantilla is the Chief Researcher in HURIGHTS OSAKA.

For further information, please contact: HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes

1 Toshio Mizuuchi, "Changing urban governance for socially discriminated people: A case of Osaka City, Japan," in Proceedings of 2nd.International Critical Geography Conference, Korean Association of Spatial Environment Research, 181-188, 2000, available at www.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/geo/mizuuchi/english/e_material/mizuuchi_in_Taegu.htm.

2 Mizuuchi, ibid.

3 Kamagasaki Community Regeneration Forum, www.kamagasaki-forum.com/en/.

4 Sen Arimura, "The History of Kamagasaki: After 1945," Kamagasaki Community Regeneration Forum, www.kamagasaki-forum.com/en/index.html.

5 This is a quotation from additional material on "The History of Kamagasaki: After 1945," provided by Sen Arimura by e-mail on 26 August 2019.

6 Tatsuya Shirahase, "Dilemma over the Redevelopment of Poor Areas: A Case Study of Airin District," in Human Welfare Studies 10 (1), 2017. 12.

7 Shirahase, "ibid.

8 Arimura Sen, "The History of Kamagasaki: After 1945,” op. cit.

9 Shirahase, op. cit.

10 Arimura, additional information, op. cit.

11 Shirahase, op. cit.

12 Sen Arimura Sen, “What is a service hub? No. 2. ([English translation) Service Hub Theory) Fukushino Hiroba, 2018. Material received via e-mail from Sen Arimura on 26 August 2019.

13 Shirahase, op. cit.

14 Machizukuiri is the Japanese word for urban renewal. See Toshio Mizuuchi and Hong Gyu Jeon, "The new mode of urban renewal for the former outcaste minority people and areas in Japan," Cities, 2010, doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.03.008, pages 3 - 4, www.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/geo/mizuuchi/japanese/material/mizuuchi_jeon_Cities.pdf.

15 Shirahase, ibid. Shirahase uses the name “Meeting on Community Creation” instead of Airin District Community Development Forum in his 2017 article.

16 Panel of Experts, “Our position on the present situation of the closing (rebuilding) of Airin Sogo Center Clarification of the measures taken and controversial points.” (undated) Document received via e-mail from Sen Arimura on 22 August 2019.

17 Airin Machizukuri Kaigi,(英語版)まちづくり会議ポスター&委員名簿 ([English version] Machizukuri Conference Poster & Committee). Material received via e-mail from Sen Arimura on 26 August 2019.

18 Panel of Experts, op. cit.

19 Panel of Experts, ibid.

20 Panel of Experts, ibid.

21 Airin Machizukuri Kaigi, op. cit., material received via e-mail from Sen Arimura on 26 August 2019.

22 Panel of Experts, op. cit. Nishinari Special District Panel of Experts:

1. Sen Arimura (Director, Kamagasaki Regeneration Forum)

2. Seiji Terakawa (Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, Kindai University)

3. Hiroyuki Fukuhara (Professor, Osaka City University)

4. Toshio Mizuuchi (Professor, Osaka City University Urban Research Center)

5. Tatsuya Shirahase (Associate Professor, Department of Sociology Momoyama Gakuin University)

6. Tanasuke Nagahashi (Professor, Department of Industrial Sociology, Ritsumeikan University,)

7. Yoshihisa Matsumura (Professor, Department of International Tourism, Hannan University).

23 Panel of experts, Suggestions from experts about Nishinari Special Zone Initiative: Town Development Vision 2018 - 2022, document received via e-mail from Sen Arimura on 26 August 2019.

24 The external forces may refer to urban development, construction and other companies that build structures in urban areas for housing and commercial purposes.

25 One definition of gentrification is this: "the process of repairing and rebuilding homes and businesses in a deteriorating area (such as an urban neighborhood) accompanied by an influx of middle-class or affluent people and that often results in the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents." Merriam Webster, https://merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gentrification.

26 Panel of experts, Suggestions from experts about Nishinari Special Zone Initiative: Town Development Vision 2018 – 2022, op. cit.