- TOP

- 国際人権基準の動向

- FOCUS

- December 2014 - Volume Vol. 78

- Workshop on Human Rights Centers in the Asia-Pacific

FOCUS December 2014 Volume Vol. 78

Workshop on Human Rights Centers in the Asia-Pacific

HURIGHTS OSAKA’s reason for existence lies in its objective of promoting human rights in Japan and in the Asia- Pacific region. In pursuing this objective, it sees the value of advocating for support for institutions in the region that gather, process and disseminate human rights information. HURIGHTS OSAKA has been compiling since 2001 information on institutions in Asia-Pacific that are considered “human rights centers.”1

HURIGHTS OSAKA published in 2008 a directory of almost two hundred human rights centers, followed by an updated version in 2013. Through this project, HURIGHTS OSAKA has been able to establish contact with almost three hundred human rights centers in West, Central, South, Southeast and Northeast Asia, and in the Pacific.

The two editions (2008 and 2013) of the Directory of Asia- Pacific Human Rights Centers show the variety and comprehensiveness of the programs and activities being implemented by these human rights centers.

The human rights centers, and institutions that have “human rights center” function, in the Asia-Pacific deserve recognition and continued support. They exist in significant number in the region and play important roles in their respective constituencies.

HURIGHTS OSAKA saw the need to review the experiences of some of the human rights centers in line with its 20th anniversary in December 2014. It organized a small workshop on human rights centers on 13 December 2014 in Osaka.

Human Rights Centers: An Overview

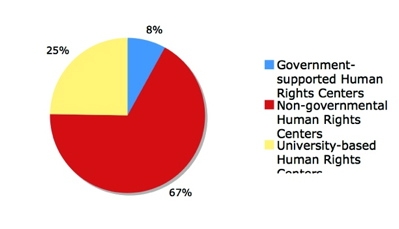

The profiles of almost two hundred fifty human rights centers in Asia and the Pacific in the 2013 edition of the Directory of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers show three major categories of centers: non-governmental, government- supported and university-based.

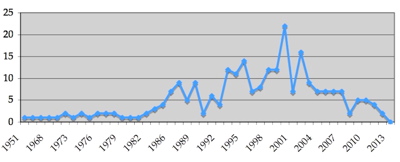

These profiles show that some centers started way back in the late1950s; while a majority of them were established from late 1980s to mid-2000s (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Timeline in Establishment of Human Rights Centers

Figure 2. Number of Human Rights Centers per Major Category

Majority of these centers are non-governmental in nature (around 67 percent of the listed centers), followed by university- based centers at 25 percent and government-supported centers at 8 percent2 as seen in Figure 2 above.

The human rights centers generally undertake the following tasks:

-

• Research on very particular issues regarding

- o Sectoral groups - women, indigenous peoples, minorities, etc.

- o Thematic concerns - human rights violations, particular rights (right to development, housing rights), larger issues (armed conflict situation/ peace, development, democracy, etc.)

- o Overlapping themes - human rights and democracy, human rights and environment, human rights and peace, human rights and business, etc.;

- •Analysis of measures (international and national) that support human rights protection, promotion, realization; preparation of proposals for reform (in terms of proposed laws, policies, programs, and particular actions) in the systems affecting human rights;

- • Dissemination of knowledge on the international human rights standards and mechanisms, relevant local laws and processes;

- • Exposition of, and promotion of public discussion on, human rights issues.

In general, the collected human rights information may become

- • Content of advocacy and educational materials to sensitize the public on specific issues, and other human rights promotion activities;

-

• Bases for

- • Raising the visibility of certain rights (such as rights of specific sectors – women, children, urban poor, farmers, etc.)

- • Assessing new areas of rights violations

- • Exploring new areas of work according to changing contexts (such as development of new programs)

- • Determining strategic interventions (such as resort to judicial remedy) in particular cases

- • Ensuring clarity of perspective in monitoring human rights violations (such as adoption of particular issues as focus of monitoring program).

Workshop Proceedings

The workshop reviewed the current programs and activities of human rights centers in some countries in the Asia-Pacific, discussed key elements that define the work of these centers in relation to particular themes; and identified challenges and opportunities facing the human rights centers in pursuing the goal of promoting human rights at various levels (community/ city/province, national, regional).

The workshop focused on four themes of human rights center work:

- a. Documentation – review of the core functions of a human rights center consisting of gathering, processing and disseminating information;

- b. Community action – examination of the dissemination function of a human rights center through service provision;

- c. Working with local government - discussion of the significance of working with local government especially for a human rights center that covers a local area;

- d. Education – presentation on the important role of facilitating education of people on the meaning and practice of human rights.

Discussions on the themes were initiated by the representatives of the following human rights centers:

- a. Documentation - Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam);

- b. Community action - Psychosocial Support and Children’s Rights Resource Center (Philippines);

- c. Work with local government - Tottori Prefectural Center for Universal Culture of Human Rights (Japan) ; and

- d. Education - HURIGHTS OSAKA (Japan).

Documentation

The establishment of theDocumentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) started with the Cambodian Genocide Program (CGP) in Yale University and the subsequent creation of a branch office in Phnom Penh. The program started a study in 1994 of the events under the so-called “Cambodian genocide of 1975-1979” to “learn as much as possible about the tragedy, and to help determine who was responsible for the crimes of the Pol Pot regime.”3 The program has compiled thousands of materials (documents, photos, etc.) related to the Khmer Rouge (KR) era.4 This program led to the establishment of DC-Cam in 1997 as an independent Cambodian non-governmental organization with twin objectives: Memory and Justice.

DC-Cam has continued compiling information on the KR era organized into the following databases:5

- a. Bibliographic Database - 2,963 records entered by DC-Cam and CGP consisting of confessions collected from prisoners detained in the Khmer Rouge prison at Kraing Tachann in Takeo province, as well as other sources. They include interviews, books, articles and primary documents;

- b. Biographic Database - 30,442 biographies of victims (ordinary citizens), KR commanders, cadres, soldiers, medical staff, messengers, militiamen, and other KR members, including those imprisoned and tortured in Tuol Sleng (S-21) prison;

- c. Photographic Database – 5,190 photographs of prisoners from Tuol Sleng (S-21) prison in Phnom Penh;

- d. Geographic Database – consisting of the map that indicates places where the killings occurred during the KR era.

There are also three hundred documentary films in the DC- Cam collection.

The collection of information has enabled DC-Cam to undertake the following programs and projects:

- • Forensics, Mapping the Killing Fields;

- • Affinity Group (network of documentation centers in the former Yugoslavia, Guatemala, Burma [headquartered in Thailand], Iraq, Afghanistan, and South Africa to share information and techniques, and work together to address the constraints shared by its members);

- • Legal Training, Response Team, Victims Participation, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) Trial Observation;

- • Living Documents;

- • Magazine (Searching for the Truth);

- • Promoting Accountability;

- • Public Information Room;

- • Oral History Project;

- • Victims of Torture Project;

- • Witnessing Justice Project;

- • Genocide Education Project.

These programs and projects address a variety of concerns from providing support to the ongoing trial of KR leaders, to helping surviving family members of victims find their relatives, to making the Cambodians in general properly understand the KR issue.

Community action

The Psychosocial Support and Children’s Rights Resource Center (PST CRRC) started in 1993 as a special program under the Peace, Conflict Resolution, and Human Rights Program of the Center for Integrative and Development Studies of the University of the Philippines (UP CIDS PST). The special program facilitated the mainstreaming and institutionalization of psychosocial trauma and human rights concerns in the academe. In 2006, the special program was converted into PST CRRC, a non-governmental organization. PST CRRC engages in research, training, advocacy, networking, and providing up-to-date and relevant materials and resources on psychosocial support and childhood, and child rights. PST-CRRC has been providing services to local communities that suffer from natural disasters, armed conflict, violence and similar events. It implements a community-based and participatory approach that

- • Involves community members in the conceptualization and implementation of programs and activities for children;

- • Assumes that communities have their own resources and strategies for helping themselves; and

- • Assumes that children are not only vulnerable victims and passive recipients of assistance but also active agents in their own recovery and for community development.

Using this approach, PST-CRRC provides psychosocial interventions that address people’s thoughts, feelings, attitudes and behaviors in the context of social, economic, cultural, and spiritual factors that affect them. Regarding children, the PST-CRRC programs address an “umbrella of rights” based on the principles in the Convention on the Rights of the Child:

- • The best interests of the child (Article 3.1)

- • Non-discrimination (Article 2)

- • Participation (Article 12)

- • Fulfilment of child rights (to the maximum extent of available resources) (Article 4)

- • The right to life, survival and development (Article 6).

The activities take the form of specific and practical actions (such as equipping children and young people with knowledge and skills on disaster risk reduction, and facilitating the participation of children in community projects and development efforts), strengthening structures and mechanisms (such as working with existing community organizations and programs, specifically with child- and youth-led organizations), and awareness-raising/building constituencies of support within the communities.

Working with the local government

The Tottori Prefectural Center for Universal Culture of Human Rights was established in 1997 to implement the objectives of the Tottori Prefectural Ordinance for Creating a Pro-Human Rights Society and the subsequent Tottori Prefectural policies on human rights to create a society where human rights and civil liberties are respected. It is financially supported by the local governments (prefectural and town) in Tottori prefecture. It has member-institutions consisting of local governments and private organizations.

The Center works with local governments by providing lecturers to their educational programs; assisting them in organizing human rights study meetings; disseminating human rights information to the general public through its website, and through newspapers, e-mail magazine, and blogs; distribution of informational/ educational materials; and implementation of projects (such as organizing of Tottori Cartoon Award and management of the Tottori Prefectural Human Rights Space 21). The Center has been working on a number of issues including the Buraku issue, women’s rights, rights of people with disabilities, child rights, rights of the elderly, and migrant rights.

Despite the financial difficulties of the local governments in Tottori prefecture, the Center continues to receive financial support from them.

Human rights education

HURIGHTS OSAKA, a local institution with a regional human rights program, has been implementing a regional human rights education program since the latter part of the 1990s in collaboration with institutions and individuals in various countries in Asia. Its regional human rights education program consists of information collection through research, processing the information in the form of various types of publication (research reports, annual publications, teaching- learning materials), and disseminating them (through training workshops, participation in meetings and conferences, and online modes). A major component of the regional human rights education program of HURIGHTS OSAKA is the documentation of human rights education programs and experiences in various countries in Asia and the Pacific. The database on human rights education is focused on Asia and the Pacific and aims to serve the needs of human rights educators in the region.6 The database is continuously though slowly being built as HURIGHTS OSAKA gathers information and materials on human rights education.

Key Issues and Challenges

Human rights centers in general gather and process data related to human rights to support their aim of helping people gain appropriate understanding of human rights and human rights issues, and facilitating action on human rights issues as maybe necessary. The DC-Cam program provides a good model of documenting a specific human rights issue with clear aims of supporting efforts to hold human rights violators accountable, and of making people learn from, and remember, the experience. Such human rights data are also necessary in seeking reform in government policies and programs.

In carrying on with the tasks of gathering and processing data, the human rights centers are concerned about the security of the data. DC-Cam, for example, secures its data by digitalizing them and keeping copies in several places. But the security, in this sense, can also refer to assurance that the data are made available for public use for a long period of time. Necessarily, they also need to provide the space (physical and digital) and activities for people to access human rights information, talk about them, and use them.

In terms of opportunities, human rights centers use

- a. Human rights policies (including local government ordinances or action plans related to human rights) as bases for working with governments and also as political support from governments as shown by the experience of the Tottori Prefectural Center for Universal Culture of Human Rights;

- b. Community resources including households that facilitate transmission of human rights information to family members (Tottori Prefectural Center for Universal Culture of Human Rights), and existing community institutions to help sustain human rights initiatives (such as working with religious institutions [Buddhist temples and Christian churches] and local non-governmental organizations in the cases of DC-Cam and PST-CRRC);

- c. Human rights-related materials (reports of activities, research reports) of any institution or group that qualify for wider dissemination. This is seen in the case of HURIGHTS OSAKA’s practice of seeking out such materials and processing them for publication and other forms of dissemination in support of human rights education;

- d. Networking with relevant institutions or groups to support the programs. This is seen in the human rights education work of DC-Cam in terms of partnership with the Ministry of Education, Science, Youth and Sports of Cambodia, or in working with private corporations and local governments in holding the annual human rights training program of the Buraku Liberation and Human Rights Research Institute (Japan). This can also refer to recognizing the human rights component of institutions that work on other issues (such as peace, development, environment, etc.) and finding ways to collaborate with them.

Human rights centers face a number of challenges7 that affect their operations. These challenges may refer to the following:

- • Conceptual: overcoming notions about people and human rights that can either deprive people of their rights (such as when children are considered to be the object of protection only and not subject of participatory process to fulfill their rights) or make people see human rights as irrelevant to their daily life (such as when human rights are considered to be exclusively referring to major political issues);

- • Political: linked to the conceptual challenge, adopting approaches that do not cause inappropriate rejection by people and government of human rights or human rights work. Such approaches may have to be non-confrontational and entails “strategic diplomacy” or friendly engagement ( especially with governments);

- • Security: ensuring that human rights data are not lost such as by digitizing and duplicating them (similar to the digital KR documents that are safeguarded in three American universities);

- • Donor and NGO politics: finding ways to address the political agenda of donors and also NGOs that may deviate from the objectives of human rights centers; finding proper stance in building networks of related institutions that have differing agenda;

- • Resources: ensuring continued support for the operations of the human rights centers, despite changing political environment;

- • Academic agenda: finding ways of supporting all academic initiatives (even those critical of humanrights concept and practice) through provision of human rights materials;

- • Technological: employing and maintaining technologies suitable to the work of human rights centers;

- • Programmatic – developing program implementation processes that effectively ensure respect for human rights (such as respect for the participation of children in activities affecting them), avoiding token gestures of respect for human rights in these processes; establishing new programs that can be sustained over a significant period of time and relevant to the needs of the human rights centers’ constituencies.

The most significant and difficult challenge to human rights centers is on making impact on people and community who are considered to be the main beneficiaries of their work. Human rights centers have to learn from each other’s experiences in addressing these challenges.

For further information, please contact HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes

1. The two editions (2008 and 2013) of the Directory of Asia- Pacific Human Rights Centers define a human rights center as an institution engaged in gathering and dissemination of information related to human rights. The information refers to the international human rights instruments, documents of the United Nations human rights bodies, reports on human rights situations, analyses of human rights issues, human rights pro- grams and activities, and other human rights-related information that are relevant to the needs of the communities in the Asia-Pacific.

2. Figure 2 includes data on almost one hundred fifty other centers that are listed in the 2013 edition of the Directory but do not have complete organizational information.

3. Cambodian Genocide Program (CGP), Yale University, www.yale.edu/cgp/.

4. The website of the CGP states: In Phnom Penh in 1996, for instance, we obtained access to the 100,000-page archive of that defunct regime's security police, the Santebal. This material has been micro-filmed by Yale University's Sterling Library and made available to scholars world- wide. As of January 2008, we have also compiled and published 22,000 biographic and bibliographic records, and over 6,000 photographs, along with documents, translations, maps, and an extensive list of CGP books and research papers on the genocide, as well as the CGP's newly-enhanced, interactive Cambodian Geographic Database, CGEO, which includes data on: Cambodia’s 13,000 villages; the 115,000 sites targeted in 231,00 U.S. bombing sorties flown over Cambodia in 1965-75, dropping 2.75 million tons of munitions; 158 prisons run by Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge regime during 1975-1979, and 309 mass-grave sites with an estimated total of 19,000 grave pits; and 76 sites of post-1979 memorials to victims of the Khmer Rouge.

5. These databases are accessible online:

- • Biographic Database - http://d.dccam.org/Database/Biographic/Cbio.php

- • Bibliographic Database - http://d.dccam.org/Database/Bibliographic/Cbib.php

- • Photographic Database - http://d.dccam.org/Database/Photographic/Cts.php

- • Geographic Database - http://d.dccam.org/Database/Geographic/Index.htm.

The information can also be accessed in this page: http://d.dccam.org/Archives/Documents/Documents.htm.

6. See materials on human rights education in HURIGHTS OSAKA website

(www.hurights.or.jp/english/overrview-human-rights-education-in-the-asia-pacific.html), and related publications in www.hurights.or.jp/english/publication.html.

7. The discussion on challenges combines the ideas expressed in the presentations by human rights centers’ representatives (Khamboly Dy of DC-Cam, Agnes Zenaida V. Camacho of PST- CRRC, Mariko Ozaki of the Tottori Prefectural Center for Universal Culture of Human Rights, and Jefferson R. Plantilla of HURIGHTS OSAKA) and other workshop participants.