- TOP

- 国際人権基準の動向

- FOCUS

- September 2013 - Volume Vol. 73

- Local and Community-Led Conflict Monitoring

FOCUS September 2013 Volume Vol. 73

Local and Community-Led Conflict Monitoring

The 9 September 2013 Displacement Alert entitled “Fighting in Zamboanga City” records the events of that morning:1

At around 5:00 a.m. today, September 9, 2013, a gunfight erupted between AFP [Armed Forces of the Philippines] troops and alleged members of the MNLF [Moro National Liberation Front] at Barangay [community] Rio Hondo, Zamboanga City. Residents from Barangay Rio Hondo and the nearby barangays of Sta. Barbara, Sta. Catalina, and Mariki were reported to have been trapped in the area.

At around 6:00 a.m., MinHRAC's staff from Zamboanga Satellite Office (ZSO) arrived at the field to conduct a verification mission.

Per our colleagues, who were just meters away from the frontline, many of the residents found it difficult to move to safety as the gunfight broke out while they were still in bed and woke up amid gunfight.

Further, at around 8:00 a.m., the fighting spread to the nearby barangay of Sta. Barbara. Then at around 10:00 a.m., the fighting reached the Barangay of Sta. Catalina.

Per the team also, [a] M79 grenade launcher exploded at Barangay Sta. Catalina at around 9:05 a.m., allegedly killing a soldier from the AFP. Further, as the skirmishes shifted from one area to another, one more barangay was affected by the fighting, in addition to the 4 aforementioned affected barangays. Residents of this barangay of Talon-talon were unable to move for fear that the gunfights might move into their barangay and that they might get caught in the crossfire.

According to the team also, they had to use their vehicle to shield a family of 8, including 5 minors, trapped earlier in Barangay Sta. Catalina.

The fighting subsided at around 10:45 a.m., allowing some residents to move out of their affected barangays. However, many [were] still rapped in their residences out [of] fear that firings [might] continue to occur.

MinHRAC- ZSO staff are now in identified evacuation sites to gather related information.

Another report on 16 September 2013 states:

The residents of the villages that needed flash protection alert due to the artillery shelling yesterday reported that it [had] already ceased. Up until 2 p.m., we have not heard of any reports of resumption of shelling.

These reports provide a picture of the quick response of a team from the Mindanao Human Rights Action Center (MinHRAC) when encounters between government soldiers and members of the armed opposition occur. They also present the role played by members of affected communities in monitoring the situation.

Conflict Monitoring in Mindanao

All throughout the 2008-2009 humanitarian emergency situation in the Bangsamoro areas,2 there was a running debate on the basic information about the internally displaced persons (IDPs) - how many persons were involved, which villages where they from, where did they evacuate, who were they, etc. There was a huge uncertainty on who needed food relief goods, and how many IDP tents had to be built. Even when most of the IDPs have returned home, how many lost their homes and who needed help to rebuild them remained unanswered.

Reports about the emergency situation cite 120,000 deaths resulting from the conflict. But this number had been cited since the 1980s and it is still being used as reference figure for the total number of deaths in current literature. One researcher pointed this out and observed that “considering the fact that many more have died in the last 20 years it is evident that there is no systematic data [collection] on the death toll”. 3

Regarding employment, the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (comprised of Lanao de Sur, Maguindanao, Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-tawi provinces) registered the lowest unemployment rate (2.7 percent) among all regions of the Philippines during the large- scale violence between the GRP and the MILF in 2008. However, mainstream media has not cited this information.

These are examples of the glaring flaws in conventional data generation about the conflict-affected Bangsamoro communities, including data about IDPs.

Monitoring Conflict Situations: Challenges

The conflict in Mindanao involving Moro rebel groups affects a total of 3,831 barangays (villages), in one hundred fifty municipalities (towns), spread out over thirteen provinces.4 This is the size of the area that needed to be monitored. Many of these barangays are highly inaccessible. To illustrate the point, the mediation of a year- old clan feud in a community fifty kilometers away from Cotabato City required the mediation team a half-day ride through rough dirt roads in the mountains to reach the community.

The problem of physical access is compounded by the lack of fast means of communications. Outside its capital town of Jolo, communication by mobile phone to or from Sulu province is difficult. And even in the center of the capital town, fax and e-mail are problematic. Providing monitors with hand- held radios is both costly and unwise. Hand-held radios are a magnet for rebels, who have an even greater tactical need for them.

There are obviously security concerns to worry about.

A person from Maguindanao province might have enough links with the local people to enable her/him to visit various parts of the province. But visiting local places in another province would not necessarily be possible for such person, moreso if he or she was not a Moro.

Assuming all these access issues have been hurdled, the next challenge is on defining the monitoring strategy, which is determined by the object of the monitoring.

What is being monitored? - The incidence of violence? The number of IDPs? The number of homes burned? Who is involved in the violence? - The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces (BIAF)? AFP and the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)? Rival politicians? Civilian Volunteer Organizations (CVOs) and the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Unit (CAFGUs)? Is a specific violent incident between the Ampatuan CVOs and the 105th Base Command of the BIAF just another clan feud or a proxy war between the AFP and the BIAF? How does one classify a confrontation where members of the MNLF, ASG, and local Philippine National Police (PNP) unit are ranged against the Philippine Marines? Is this still counter-insurgency incident? The conflict in the Bangsamoro areas is of such type that many of the incidents of violence are not necessarily between the military and the mainstream Moro liberation movement. And even if they were involved, there is no certainty on their motivations for engaging in the violent acts. Is the military upholding the duty to defend the state, and is the other side fighting for the right to self-determination? Or, are they motivated by something else?

The biggest challenge in monitoring the conflict in the Bangsamoro areas lies in the fact that the conflict is a very complex situation. Thus the interpretation of an incident can be a problem. As most of those who have had an in-depth experience in responding to emergencies, a wrong reading of an incident can lead responders to a wrong decision or action which creates more harm than good.

Past and Existing Monitoring Mechanisms

The peace agreement mediated by the Organization of Islamic Countries and signed in 1996 by the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) led to the deployment of a team of Indonesian monitors to Mindanao. This monitoring team, with the support of a major multilateral organization, operated from 1996 to 2001. In 2001, it reported to the OIC that the implementation of the agreement was going well save for a few minor problems. However, one “minor” problem turned out to be the decision of the MNLF leader, Nur Misuari, to go back to the hills and his declaration of war against the government.

On the other hand, soon after signing a Cessation of Hostilities Agreement in 1997, the GRP and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) constituted their respective Ceasefire Committees, primarily to coordinate their respective forces' movements but also to monitor the implementation of the agreement. But fighting broke-out from 1998 onwards, which showed the agreement's inherent weakness. For each violent encounter between their armed forces, both sides blame the other for starting the fight.

The International Monitoring Team of the GRP-MILF Peace Process (IMT) is by far the most well-known among existing monitoring mechanisms. It enjoys the advantage of being officially recognized by both the GRP and MILF. As a third party, it performs the role of "referee". Further, being made up of representatives of foreign governments, the reports of IMT are accorded weight. This privilege is not available to non- governmental conflict monitoring entities. IMT's main disadvantage though is the lack of monitors. As of last count, IMT has thirty-nine monitors deployed in four field sites to cover the entire conflict- affected region.

Government agencies are sources of data about the conflict, but their data have problems as shown earlier. The local media can provide data, but its limited presence in the provinces involved is a huge disadvantage.

Grassroots Led and Operated Monitoring to Fill in the Gaps

There is still much to do in gathering reliable and comprehensive data on the armed conflict in Mindanao. And there is a need to search for additional data sources to complement existing ones. The residents in the conflict-affected communities are a monitoring resource that has unjustly been downplayed. These residents are the first to know about any incidence of conflict, and are in the best position to interpret it. And most of all, they have the biggest interest in reporting it.

To avoid the impression that they are being exploited for monitoring purposes, it is important that they have a real stake and participation in the monitoring and data generation process. The residents should have the autonomy to decide on the deployment of monitors, trending and forecasting, and many other issues. They can be supported with information on common monitoring template, and other tools.

Thus, in relation to the operations of the Civilian Protection Component (CPC) of the International Monitoring Team (IMT), the involvement of the Moros is a must. The Moros comprise 85 percent of those affected by the conflict being monitored by the IMT-CPC. They should be participating in the meetings of the IMT-CPC.

Empowering Conflict Affected Communities

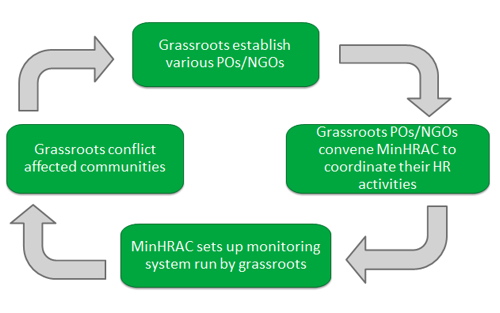

MinHRAC promotes the idea of empowering the residents of communities affected by the conflict. The residents of the communities are encouraged to form their own organizations that can coordinate their human rights activities with MinHRAC.

MinHRAC in turn establishes a monitoring system to be run by community organizations.

This idea of community-led monitoring system is illustrated below.

The interests of the residents in the conflict-affected areas permeate the entire structure.

Grassroots Monitors

The case of a community volunteer provides an example of how the system works. Jocelyn Basaluddin, a thirty- nine year old mother, “learned from years of working with nongovernment organizations as a volunteer relief worker and from journalists she met” what to do regarding families displaced by violence in Sulu.5 She found that many of them “knew nothing about their rights. So I started teaching them basic human rights through casual conversations.” She established a network of contacts and sent them mobile phone text messages every day. Whenever she received information on “possible complaints of human rights abuses,” she forwarded the information to MinHRAC.

The news report further explained the support from community volunteers:6

Today, Basaluddin's network has grown to 49 village-based monitors - students, drivers and even ordinary housewives - in Sulu's 19 towns. Among their biggest contribution was the filing of human rights violations against several government personalities, including soldiers, at the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

In Basilan, 25-year-old Radzmi e Hanapi , a criminology graduate, said he had had enough of abuses. "I was doing volunteer work for NGOs and saw some of the abuses myself," he said.

Hanapi cited the case of people in Yakan communities being deprived of their rights to shelter and abode in the aftermath of the 2007 clashes in Al-Barka, which resulted in the killings of 14 Marine soldiers. This strengthened his resolve to teach people their rights, even though he was not receiving any remuneration and was courting risks, especially from violators themselves.

Basaluddin saw as very important the presence of a grassroots monitor. "The military can always restrict entry into affected areas and outside monitors would have a hard time knowing what's happening inside. In this case, the presence of a grassroots monitor is really helpful," she said.

MinHRAC values the role of the grassroots monitors in helping human rights groups advance the protection of affected people. It also recognizes the danger they face, and thus it coordinates with government agencies on their security.

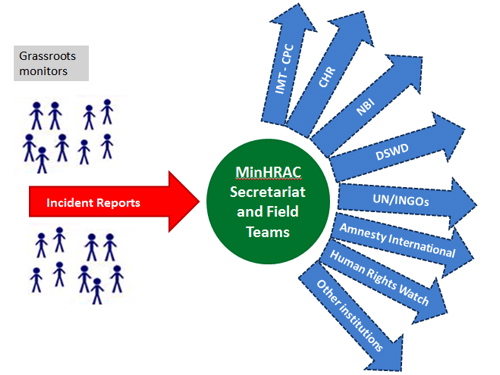

Going Beyond Mere Monitoring: Action Centers

Key to sustaining the interest of the residents in monitoring activities is the existence of benefit for their efforts. Rather than simply satisfy the request of outside monitors for information, the provision of appropriate intervention as a consequence would serve the interest of the residents. Thus came the idea of Action Centers as an initiative complementing monitoring. The Action Centers do not only encode field data but also process them to determine the appropriate type of intervention as shown in the illustration below.

For instance, the MinHRAC Secretariat, besides functioning as a recipient of alerts also functions as an Action Center. Depending on the nature of the incident, a specific protocol is put into action. Ceasefire violations are immediately referred to the International Monitoring Team and the Coordinating Committee for the Cessation of Hostilities, medical needs of civilians are immediately referred to partner humanitarian organizations, displacement alerts are forwarded to the Philippine Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), human rights violations are referred to the Commission on Human Rights, etc.

MinHRAC’s membership in the Civilian Protection Component of the GRP-MILF Peace Process can give these communities a tool by which they can communicate their security concerns to the groups most responsible or having the most impact on such concerns. Further, as a sitting member of the Protection Working Group of the United Nations System and International Non- Governmental Organizations operating in Mindanao, MinHRAC affords the communities a means to convey their humanitarian needs to the agencies concerned. Lastly, MinHRAC itself in tandemwith the Commission on Human Rights directly provides human rights and legal aid. Through these modes, MinHRAC hopefully can give back something to the communities. After all, MinHRAC traces its origin to the grassroots communities and it is only appropriate that these communities be the first clienteles.

The role of organizations such as MinHRAC has been recognized. A recent report states:7

Locally founded organizations like the Mindanao Human Rights Action Center (MinHRAC) have well- functioning networks of local volunteer monitors and professionals who are trained to provide accurate and relevant assessment of humanitarian needs and developments in their communities. This knowledge, for instance on new IDP camps, is further shared with international humanitarian organizations and the local authorities. During the current crisis, the role of grassroots organizations like MinHRAC has been instrumental in attending to the needs of civilians in Basilan and some areas around Zamboanga, which are otherwise inaccessible to international and national organizations. MinHRAC’s information campaign also helped in deterring possible disinformation campaigns, which have previously been frequently used in Mindanao to the detriment of stability.

MinHRAC has been providing almost daily news alert via internet on the situation of the IDPs in the Bangsamoro areas. This and other services of MinHRAC will continue as the conflict situation continues.

Zainudin S. Malang is the Executive Director of MinHRAC.

For further information, please contact: Mindanao Human Rights Action Center (MinHRAC) Headquarters, #66 Luna Street, Rosary Heights 4, Cotabato City, Philippines 9600; ph/fax (63-64) 390-2751; e-mail: mail@minhrac.org; http://minhrac. ph; http://facebook.com/MinHRAC.Official.

Endnotes

1. Zamboanga Crisis: Consolidation of Alerts/ Updates from September 9 to 16, 2013, Monitoring Mindanao, MinHRAC.

2. These are the provinces of Maguindanao, Lanao del Sur, Lanao del Norte, Sulu, Basilan, and Tawi-Tawi.

3. Masako Ishii, The Southern Philippines: Exit from 40 Years of Armed Conflict, P’s Pod, at http://peacebuilding.asia/southern-philippines-exit-armed-conflict/#return-note-572-3, last visited on 10 October 2013. Ishii writes:

The death toll in the last 40 years of conflict is said to have been over 120,000...However, the death toll reported in the mid- 1990s has also been 120,000. Considering the fact that many more have died in the last 20 years it is evident that there is no systematic data [collection] on the death toll.

Ivan, Molloy, “The Decline of the MNLF in the Southern Philippines,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 18:1, 1988, 59-76, page 62:

The subsequent secessionist struggle quickly engulfed the southern Philippines in a conflict that proved staggering in terms of devastation and cost. Estimated figures vary, but many claimed that by the end of the seventies the conflict had resulted in the death of over 100,000 people, and the creation of half a million refugees. The total cost was estimated to be in the billions of dollars.

Abdurasad Asani, "The Bangsamoro people; a nation in travail," Journal Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs 6(2), 1985, 295- 314. On page 310, citing Dr. Parouk Hussein's testimony before the Permanent People's Tribunal:

In the last ten years of the conflict in southern Philippines more than "100,000 innocent Moro lives, mostly children, women and the aged, have already perished; about 300,000 dwellings burned down, incalculable worth of properties wantonly destroyed and almost half of the entire population ... uprooted from their homes, including over 200,000 refugees now in the neighboring state of Sabah". [52] By the end of 1983, MNLF casualty figure had risen to 130,000.

For the Philippines, the struggle has certainly eaten up vast chunks of her resources."

Footnote 52: Dr. Parouk Hussein, in Testimony before the Permanent People's Tribunal. See, among others, A Brief Report: The Permanent People's Tribunal Session in the Philippines, (Antwerp, Belgium: Komite ng Sambayanang Pilipino, 1980) page 28.

4. This covers the Bangsamoro areas (note 1 above) plus other provinces in Mindanao.

5. Julie Alipala, “In Sulu, human rights work starts with letting the people know,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/166693/in-sulu-human-rights-work-starts-with-letting-the-people-know#ixzz2gcMp2UUI.

6. Ibid.

7. Martina Klimesova, “Local Capacity Building and The Current Crisis in Mindanao,” Policy Brief, No. 132, 27 September 2013, page 2. Full report available at www.isdp.eu/publications/policy-briefs.html.