- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- September 2008 - Volume 53

- ASEAN and Human Rights

FOCUS September 2008 Volume 53

ASEAN and Human Rights

*Jefferson R. Plantilla is a staff of HURIGHTS OSAKA.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) deserves both commendation and rebuke for its work during the past four decades. In terms of human rights, ASEAN has much to be criticized for.

A newspaper editorial evaluates the forty-one-year existence of ASEAN in this way:[1]

In a region laced with rivalry, a history of disputes, long standing suspicion and with no tradition of cooperation, ASEAN contributed to the maintenance of peace and the fostering of a regional framework.

As mutual trust grew, so did economic synergy in an area encompassing some 4.5 million square kilometers.

The combined gross domestic product of southeast Asia now reaches US$ 1,100 billion, with total trade valued at around US$ 1,400 billion.

In that respect, ASEAN has fulfilled its two primary purposes as stated in its declaration: To accelerate economic growth and promote regional peace and stability.

Cooperation in economic development underpinned most of the activities of ASEAN since its inauguration in 1967. It established from the very beginning numerous committees on different economic issues such as food and agriculture, civil air transportation, communication/air traffic services, meteorology, shipping, commerce and industry, finance, and tourism. At present, economic development is dealt with by a number of high-level officials through the Meeting of ASEAN Economic Ministers, ASEAN Finance Ministers Meeting, Senior Economic Officials Meeting, ASEAN Senior Finance Officials Meeting, and by numerous committees as implementing mechanisms.

Southeast Asia today still faces the challenge of overcoming poverty that affects a significant portion of its almost 600 million people and that exists side-by-side with the prosperity of its cities and in Singapore. As the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) reports:[2]

Despite good economic growth in the ASEAN region, large disparities in development outcomes between countries remain. Especially stark are the differences in health, economic and IT [information technology] connectivity achievements. The child and maternal mortality rates of Cambodia, the Lao People's Democratic Republic and Myanmar, for example, are between 11 and 47 times higher than those of Singapore. Similarly, the GDP per capita and labour productivity of Singapore is on par with developed countries, and three times as high as that of the next ranking ASEAN country on these scores, Malaysia. The GDP per capita and labour productivity of the poorer countries, Cambodia, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Viet Nam, is a mere tenth or less of Singapore's levels. The per capita use of mobile phones and the Internet in Cambodia and the Lao People's Democratic Republic is just one-hundredth of Singapore's use.

ASEAN Foreign Ministers refer to this situation as development gap among the countries in ASEAN, which they would like addressed through cooperation and integration.[3]

In sum, there is still much to do in the economic development of ASEAN member-states despite decades of cooperation among the governments, their collective partners,4and the private sector. In order to "accelerate economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region" as the 1967 ASEAN Declaration states, UNESCAP argues for a change in the ASEAN system - from cooperation to integration. It believes that

[T]rue regional integration will require all countries to achieve minimum standards of economic and social development, guided by international[ly] agreed development goals and principles, including those contained in the United Nations Millennium Declaration. The benefits of social and economic development by ASEAN countries therein need to be shared. Similarly, the ability of future generations to meet their needs should not be compromised.

An integrated system is deemed feasible on issues such as investment and financial flows, trade integration, management of international migration flows, control of communicable diseases and their spread across the borders, energy security, information infrastructure, and transportation infrastructure.

On governance, UNESCAP observes a bleaker picture:

All ASEAN countries, for example, rank amongst the bottom half of all countries of the world on the ability of their citizens to select their government and to engage in freedom of expression and association. Cambodia and the Lao People's Democratic Republic rank amongst the bottom quintile of all countries on the effectiveness of their governments, rule of law and the control of corruption; the Lao People's Democratic Republic also does so on the quality of its policies and regulations. Myanmar, in the meanwhile, ranks among the bottom five per cent of all countries on all these dimensions; it is even last on "voice and accountability".

As the newspaper editorial further declares, ASEAN has not met the "fresh aspirations" of the current generation for "[B]older goals and more exacting standards" and which make "ASEAN now seem increasingly antiquated." It further states that the noble goal of the 1967 ASEAN Declaration of "ensuring social justice cannot be secured without deference to the social and political rights of all ASEAN citizens."

ASEAN integration has started with the agreement to implement a number of measures:[5]

1.Signing of the ASEAN Charter in November 2007

2. Establishment of a Committee of Permanent Representatives to ASEAN composed of Ambassador-level representatives to be based in ASEAN secretariat from January 2009

3.Creation of the High Level Panel on an ASEAN human rights body

4. Creation of High Level Legal Experts' Group on Follow Up to the ASEAN Charter (which will discuss the legal personality of ASEAN, dispute settlement mechanisms and other legal issues).

The ASEAN Foreign Ministers expected the convening of the ASEAN Committee on the Implementation of the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers before November 2008.[6]

The human rights situation in Southeast Asia presents a major challenge to the fulfillment of ASEAN's human rights plans.

Human rights issues in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia suffers from human rights violations that occur within states and across the border. Some of the problems relate to the colonial legal framework of the 1930s-1950s period and to the national security ideology of the 1960s-1970s period. And some remain in the current legal system as shown in the case of Malaysia. Laws in Malaysia restrict the exercise of constitutionally supported human rights with The Internal Security Act of 1960 as an example of a potent legal tool for suppressing dissent. Similarly in Singapore there are legal measures that restrict fundamental liberties as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Legal Restrictions on Human Liberties and Freedom[7]

| Fundamental Liberties | Restrictions: Legislative and Policy |

| 1. Liberty of the Person * freedom not to be deprived of life * freedom from arbitrary arrest |

・Penal Code

・Internal Security Act ・Criminal Law [Temporary Provision] Act ・Criminal Procedure Code ・Misuse of Drugs Act ・Death penalty |

| 2. No Slavery and Forced Labour

* not to be held in slavery * not to be held in forced labour |

・Enlistment Act ・Prisons Act ・Criminal Law [Temporary Provision Act] |

| 3. Equality

* all persons are equal before the law and provided with equal protection of the law * right not to be discriminated against due to race, religion, descent or place of birth |

Policy on restricting marriage between Singapore citizens and work permit holders |

| 4. No Banishment

* right not to be banished |

・Banishment Act ・Immigration Act ・Internal Security Act ・Passports Act ・National Registration Act |

| 5. Freedom of Movement

* freedom to move freely and live in Singapore |

Housing policy on ethnic eligibility |

| 6. Freedom of Speech, Assembly & Association

* freedom of speech and expression * right to assemble peacefully and without arms * right to form an association |

・Sedition Act

・Undesirable Publications Act ・Newspaper and Printing Presses Act ・Penal Code ・Internal Security Act ・Public Entertainment Act ・Trade Unions Act ・Societies Act ・Mutual Benefit Organization Act ・Rules and regulations on Speakers Corner |

| 7. Freedom of Religion

* right to profess and practice religion |

Religious Harmony Act |

| 8. Education Right

* right not to be discriminated against on the basis of religion, race, descent or place of birth in relation to admission of pupils or payment of fees |

Policies on admission of children to schools, e.g., sterilization and educational achievements of parents |

Human rights violations go beyond the legal framework in the cases of extra-judicial killing, disappearances and torture, which have been reported in several Southeast Asian countries particularly in the Philippines. People considered as "enemies of the State" have suffered from these forms of violation.[8] Likewise, the Philippine government agencies have been accused of violating the rights of urban and rural poor due to demolitions and displacements caused by public infrastructural projects and business enterprises.

In the context of the significant extent of poverty in Southeast Asia, women suffer more than men due to limited access to health services, education, housing, financial services, and information. Discrimination and violence against women also figure prominently among poor women. The situation is more acute for rural women, including those who belong to ethnic minority groups.[9]

Trafficking has accompanied the migration of people to countries within Southeast Asia. Poverty and also a host of other reasons (including problems within the family, attraction to life in the city, restrictions in the local communities) are the usual reasons for migration, which traffickers exploit. Trafficking of children, men and women has affected Southeast Asia quite extensively for a long period of time. A recent report describes the situation as follows: [10]

Within the ASEAN region, Cambodian children are trafficked to Vietnam and Thailand to work as street beggars, Indonesian women are trafficked to Malaysia to work as domestic workers, Laotian men are trafficked onto Thai fishing boats, Vietnamese women are trafficked through false marriages into numerous commercial sex industries, Burmese women are trafficked to Thailand to work as domestic workers.

Migrant domestic workers in Singapore and Malaysia who come from the Philippines and Indonesia report many cases of abuse at the hands of their employers.[11]

Southeast Asia has a great number of child workers working at home as domestic help, in factories and other commercial establishments. They may migrate from rural areas to the urban centers, or cross the border to the neighboring country. These children suffer from[12]

* Working in isolation and/or being confined to the premises of the employer;

* Long working hours; open-ended and ill-defined working hours; being "on stand-by" 24 hours a day;

* No regular break times or rest days;

* Limited or no opportunities for education;

* Vulnerable to ill health due to physical and mental exhaustion, emotional trauma, etc.;

* Trafficking into domestic labour;

* [Not] [b]eing allowed ... or limited contact with out- siders and their own families; no channels to discuss or alert others to their problems; and

* Denied their rights as children to special protection and care.

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIVs) in Southeast Asia suffer from discrimination. They are discriminated in the society, groups, and within their own family.[13]Discrimination occurs most frequently within the context of health service. One survey of PLHIVs in Thailand and the Philippines shows the high rate of discrimination in the health sector at the point of testing, before they "knew they [were] HIV- positive . . . "[14]The health personnel, without the prior consent of the PLHIVs, leaked out information on the positive test result. Some of the PLHIVs were forced or tricked into testing, and many were not given appropriate explanation on the test to be done. Discrimination continues during the treatment phase.

Press freedom remains under threat in Southeast Asia. While there are positive developments supporting "political and media reform towards a more open society ...the fight to protect and promote press freedom in this part of the world is far from won." As the Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) reports:[15]

the passage of laws on "national security" and Internet-related crimes in Thailand was a familiar theme in 2007 to all countries in Southeast Asia, from Vietnam to the Philippines and Malaysia to Laos. All carry implications for free expression and press freedom, particularly in the realm of new media where, in Southeast Asia and elsewhere, many flashpoints on free expression are taking place. All highlight the uncertainties the Southeast Asian press will continue to face in the days, months, and years ahead.

Internal armed conflicts in the Philippines, and in southern Thailand, have resulted in humanitarian crises that spilled over to the neighboring country, Malaysia. Internally displaced people in the Philippines suffer as much as those who crossed the border to Malaysia, especially when the latter decides to repatriate these people who escaped from the fighting between the government forces and the rebel groups in southern Philippines. Similarly, the refugees from Burma/Myanmar along the Thai-Burma

border, and the Lao refugees along the Thai-Lao border, still face uncertainty and hardship.

The Burma/Myanmar situation remains a very grave issue in Southeast Asia.

There is also a serious problem of holding human rights violators accountable for their action. Inaction of government officials creates an environment of impunity. The slowness of the judicial systems coupled with weak political will of the governments to resolve human rights problems are serious impediments to the full respect for human rights.

ASEAN, as an organization, has hardly been seen as actively working on many of these issues.

Human rights standards

If ASEAN seriously considers addressing these human rights issues, there must be clear standards on which to base its actions. These standards are set internationally and should be applied to the Southeast Asian situation. There should not be ASEAN human rights standards, unless they are superior to the international human rights standards.

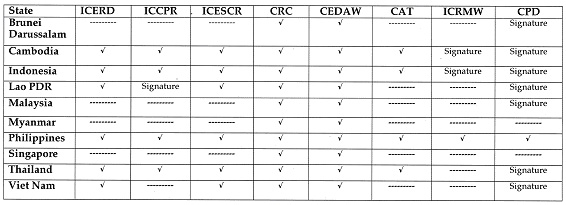

Such international human rights standards already exist, to a certain extent, in Southeast Asia. ASEAN member-states are parties to some of the core international human rights treaties. But out of eight core international instruments, only two have been ratified by all ASEAN member-states - the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Table 2 shows the status of ratification by the ASEAN member-states of the United Nations core international human rights instruments.

Table 2. Ratification of core international human rights treaties[16]

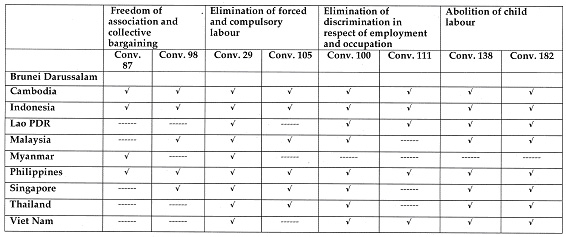

Table 3. Ratification of major ILO conventions[17]

Some ASEAN member-states have also ratified the major International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions as shown in Table 3. It is notable however that one convention (Convention 87, Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948) has not been ratified by five ASEAN member-states, while Convention 98 (Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949) and Convention 111 (Discrimination [Employment and Occupation] Convention, 1958) have not been ratified by four member-states each. Only three members-states ratified all these major ILO conventions, while one member-state ratified only two conventions.

The 2000 Joint Communiqu・of the ASEAN Labour Ministers declares the ILO conventions as standards in protecting labor rights:[18]

16.The Ministers reaffirmed their commitment to promote working conditions in an environment of freedom and equality. On the worst forms of child labour, the Ministers reiterated their position that child labour should be eliminated as soon as possible but were of the view that the solution to the fundamental problem should be through education, technical assistance and other promotional activities. On the promotion of labour standards, the Ministers stressed that it should not be linked to trade issues and registered their concern that labour standards could be used for protectionist or other purposes which are not relevant to the objectives of the ILO. In this regard, the Ministers urged the ILO to assure that the promotion of labour standards should be carried out within the purview of the ILO and for the benefit of the workers, employers and governments of the Member States.

Workers rights, being human rights, are a proper concern of ASEAN in line with its economic development focus. The ILO conventions are significant standards in protecting workers rights in Southeast Asia.

Any action on human rights issues should be based on internationally agreed human rights standards. ASEAN has declared its adherence to the Charter of the United Nations as guiding principle in its operations, and has stated in its ASEAN Charter the principle of "upholding the United Nations Charter and international law, including international humanitarian law, subscribed to by ASEAN Member States."[19] The rules in a "rules-based ASEAN" should include international human rights standards.

The use of international standards is not alien to ASEAN. ASEAN's action in the late 1980s and early 1990s on the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia, and in 2004 on the Burma/Myanmar issue were based on the need to allow the people to decide on the political leadership in government as required by international law. Also, ASEAN "encouraged all concerned parties in Myanmar to continue their efforts to effect a smooth transition to democracy."[20]

Multi-level human rights approach

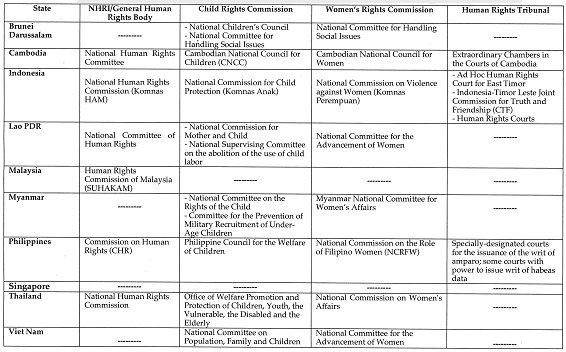

ASEAN member-states have national institutions/committees/offices/agencies whose functions range from monitoring the realization or protection of particular rights to provision of services to human rights violations victims. Many of them have the mandate to implement state obligations under the ratified international human rights instruments.

While national human rights institutions have largely been highlighted in discussing national human rights mechanisms, the other off ices/agencies that should be given equal attention. In Southeast Asia, there are government offices that deal with the two major human rights instruments ratified by all ASEAN member-states (i.e., CRC and CEDAW). There are likewise judicial entities and "truth commissions" that address the issue of documenting human rights violations and providing a basis for holding the violators accountable.

These national mechanisms, with their limitations and weaknesses,[21]should be supported or pressured into playing their part in human rights promotion, protection and realization. In the case of defunct bodies such as those related to the human rights violations in Timor-Leste by members of the Indonesian military and its Timorese allies, there are serious lessons to learn from a study of the laws that created them and their performance.[22] Table 4 provides a list of such institutions, offices and judicial bodies that address different human rights issues.

Table 4. National institutions, offices and bodies with human rights functions

In addition to these existing mechanisms, there are a number of initiatives at the Southeast Asian level regarding particular issues (such as education, trafficking, child labor, HIV/AIDS, migrant workers) that involve ASEAN governments, non-governmental organizations and international organizations (such as UNICEF, UNESCO, UNDP, and UNESCAP). The ASEAN human rights structures should build on these experiences and be able to link and coordinate these initiatives to ensure the appropriate participation of the ASEAN governments.

Human rights mechanisms

The resolution of human rights violations, particularly those involving significant number of victims of violations perpetrated by the security forces and/or government agencies, require complicated and time consuming processes. Their resolution is best achieve at the national level where victims and perpetrators are found. Thus the national human rights mechanisms should be able to provide the means to hold human rights violators accountable and the victims protected, compensated or provided with other relief measures. In the same manner, these national human rights mechanisms should support measures that realize or fulfill the human rights of the vulnerable, disadvantaged and marginalized sections of society.

But when the national human rights mechanisms are ineffective or unable to provide the services expected of them, the victims should have recourse beyond the national borders. The ASEAN human rights body is one extra-territorial recourse, in addition to the United Nations human rights mechanisms. But the functions and powers, composition of members, and the corresponding secretariat and logistical resources to be provided to the ASEAN human rights body are still unclear.

The current activities among the existing national institutions, offices and bodies at the Southeast Asian level should continue and improve even more. Their initiatives on issues affecting children, women, and other vulnerable groups deserve full support. The involvement of the different government agencies in these Southeast Asian level initiatives (such as those on trafficking, child labor, migration, etc.) should be sustained and become more intensive over time.

Political will of the governments

The effective implementation of all ASEAN initiatives on human rights depends on the political will of its member-states. There are doubts on the political will of some ASEAN member-states when it comes to human rights issues. But this problem should not hinder the human rights initiatives within Southeast Asia. The ratification of the ASEAN Charter by all ASEAN member-states, and the adoption of several human-rights-related declarations should provide the legal bases for a serious approach to addressing human rights issues.

In this case, the support/pressure from the human rights community as well as other sectors is crucial in keeping the human rights mechanisms (at national and Southeast Asian levels) agenda on the ASEAN table.

ASEAN peoples and human rights

The first clause of the ASEAN Charter that states "WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)" has a very significant meaning. It brings to the fore the primary object and subject of the document. This is almost an affirmation of the idea of "ASEAN citizens."

Will an integrated Southeast Asia also lead to a united people - the ASEAN citizens - who equally enjoy not merely economic prosperity but also social security and human rights?

Human rights are affected by the cultural, economic, political and social structures in any society. There are human rights issues in economic development measures that the ASEAN member-states undertake individually and as ASEAN. Many human rights violations occur in the context (and in a number of cases because) of economic development programs and projects. Many human rights violations occur due to undemocratic political systems. Equally notable are the social and cultural structures that traditionally lead to discrimination of sections of society.

"THE PEOPLES" of ASEAN have to have the power to take action to resolve these issues through, among others, the human-rights-rules-based structures that ASEAN should create.

For further information, please contact: HURIGHTS OSAKA, piaNPO, 3F, 2-8-24 Chikko Minato-ku Osaka 552-0021 Japan; ph (816)6577-3578; fax (816) 6577- 3583; e-mail: webmail@hurights.or. j p ; www.hurights.or.jp

Endnotes

1."ASEAN at 41," editorial, The Jakarta Post, 8 July 2008, in www.thejakartapost.com/news/2008/08/07/editorial-asean-41.html

2.Ten As One: Challenges and Opportunities for ASEAN Integration, Bangkok: UNESCAP, 2007.

3."One ASEAN at the Heart of Dynamic Asia," Joint Communique'of the 41st ASEAN Ministerial Meeting Singapore, 21 July 2008.

4. ASEAN has Dialogue Partners with whom it enters into agreements on a number of economic development projects. These Dialogue Partners are Australia, Canada, China, the European Union, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea, New Zealand, the Russian Federation, the United States of America, and the United Nations Development Programme.

5.Joint Communique',op. cit.

6. Joint Communique',op. cit.

7. Based on Think Centre, "Singapore: Constitutional Rights" in http://www.thinkcentre.org/article.cfm?ArticleID=2486

8. See Maria Socorro Diokno, "Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions in the Philippines, 2001-2006" in issue number 48 of this newsletter for more discussion on this issue. This article is also available in www.hurights.or.jp/asia-pacific/048/05.html

9. See Report on ASEAN + 3 Human Security Symposium on Women and Poverty Eradication, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan and the Association for Human Rights of Women (Osaka: Association for Human Rights of Women, 2007), for more information on the situation of women in Southeast Asia.

10. Trafficking and Related Labour Exploitation in the ASEAN Region(Utrecht: International Council on Social Welfare, 2007) page 22.

11. See the Call For Regional Standard-Setting on the Human Rights of Migrants in An Irregular Situation and Migrant Domestic Workers - Appeal to the Asia-Pacific Forum issued by the Jakarta Process on 31 July 2008 in Kuala Lumpur about the need for standards on the human rights of migrants in an irregular situation and migrant domestic workers, available in www.komnasperempuan.or.id/metadot/index.pl?id=2927

12.Ayaka Matsuno and Jonathan Blagbrough, Child Domestic Labour in South-East and East Asia: Emerging Good Practices to Combat It(Bangkok: ILO-SRO Bangkok, 2005), page 34.

13. For a survey of the stigma and discrimination suffered by PLHIVs in the Mekong region see Baseline Survey of GIPA and stigma and discrimination in the Greater Mekong Region(Bangkok: POLICY Project and APN+, 2005).

14. AIDS Discrimination in Asia(Bangkok: Asia-Pacific Network of People with HIV/AIDS, 2004), page

15.15. Slipping and Sliding - The State of the Press in Southeast Asia (Bangkok: Southeast Asian Press Alliance, 2008), page 3.

16.The information in this table on the status of ratification of the human rights instruments is based on the information found in the website of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (www.ohchr.org). The international instruments shown in Table 2 are the following: ICERD - International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination ICCPR - International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICESCR - International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights CRC - Convention on the Rights of the Child CEDAW - Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CAT - Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment ICRMW - International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families CPD - Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

17. The information in this table on the status of ratification of ILO conventions is taken from ILO website (http://www.ilo.org/global/What_we_do/InternationalLabourStandards/lang-en/index.htm) accessed on October 2008.

18.See Joint Communique' of The Fourteenth ASEAN Labour Ministers Meeting, 11-12 May 2000, Manila, Philippines, available in www.aseansec.org/8652.htm.

19.Article 2j, Principles, ASEAN Charter.

20. See Joint Communique' of the 37th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting, Jakarta, 29-30 June 2004, available in www.aseansec.org/16192.htm.

21.For an assessment of the Southeast Asian national human rights institutions see 2008 Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia(Bangkok: FORUM Asia), and available at www.forum-asia.org.

22.For a review of the Ad Hoc Human Rights Court for East Timor see ELSAM's (Institute For Policy Research and Advocacy) Final Report: The Failure of Leipzig Repeated in Jakarta, as well as the Monitoring Reports for the Ad Hoc Human Rights Court for East Timor in Jakarta, Indonesia by U.C. Berkeley War Crimes Studies Center and Institute for Policy Research and Advocacy (ELSAM) in http://warcrimescenter.berkeley.edu. For the Indonesia-Timor Leste Joint Commission for Truth and Friendship (CTF) see the "Joint NGO Statement on the Handover of the Report of the Commission of Truth and Friendship" (July 15, 2008). Also see TAPOL, http://tapol.gn.apc.org/statements/st080724.html.